There’s much in what you have to say, Philip Soos! ———>

There’s much in what you have to say, Philip Soos! ———>

THEY SHOULD BE GRATEFUL!

The Institute of Public Affairs (IPA) and their mate Wendell Cox from Demographia would probably call these people whingers, because there’s absolutely nothing wrong with urban sprawl nor its lack of infrastructure. People choosing to live in the sprawl are happy, they say.

Oh, and as for Lucy Turnbull’s idea of capturing some of the uplift in land values to pay for the provision of necessary capital works in these new locations, forget it, says the IPA.

You see, the IPA gets part of its funding from Gina Rinehart, so she who pays the piper will obviously call the tune.

I think Gina may have a bit of influence on Tony Abbott, too:-

REAL ESTATE 4 RAN$OM

If you’ve not yet seen Prosper Australia’s definitive video on the cause and cure of the financial collapse, it’s now available, free, here.

The ideas in Real Estate 4 Ransom are truly transformative. Let your friends know about it, because it’s an excellent investment in 40 minutes.

And as I post this, I hear Tony Abbott calling for the suspension of standing orders in the Australian House of Representatives because former Treasurer Peter Costello, who presided over the greatest real estate bubble in our history wasn’t appointed chairman of Australia’s Future Fund. [sigh!]

THE PROPERTY INDUSTRY CAN’T HANDLE THE TRUTH, DAVID COLLYER

IN SIMPLE TERMS

Steps taken to remedy the global financial crisis both in Europe and the US are clearly proving hopelessly inadequate, and media commentary and analysis is no better. They’re not radical enough, not getting to the root of the matter. (Latin radix, root)

Question: What have the US, most of Europe and, yes, Australia and China got in common?

Answer: They all tax labour, capital, production, thrift and enterprise and undertax land price speculation.

Question: How do economies respond to these tax signals?

Answer: Quite naturally. Property monopoly, speculation and development are favoured because that’s to where tax regimes direct people and companies. Apart from property construction in the developed west, other forms of production tend to drift offshore, to where land, labour and capital is cheaper. Growth becomes pathologically exponential in the service sector, especially in finance, insurance and real estate. (The ‘FIRE’ sector.)

Question: Did the bubble in land price burst in the US and Europe?

Answer: Yes.

Question: Will the bubbles burst in China and Australia?

Answer: Yes, they must, because of inadequate land value capture and too many taxes on productivity.

Question: Are the US and EU shifting taxes from labour, capital and productivity, onto land and natural resources in order to arrest these pathologies and turn economies around?

Answer: No. Where this is happening it’s inadequate.

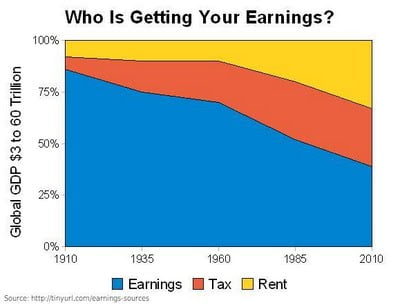

Question: Meanwhile, where are our land rents going?

Answer: To the 0.01% as usual – creating a vast wealth divide and economic depression.

Click on above model for greater detail.

AND THE CIGAR GOES TO ……………….. LUCY TURNBULL!!

CLOSE, BUT NO CIGAR

Drop the 50p tax rate and target property – the gutsy Welsh way to go

Our council tax epitomises the political cowardice of successive governments. Will George Osborne be braver?

- Simon Jenkins

- guardian.co.uk, Tuesday 6 March 2012 22.00 GMT

Billed as London’s most expensive house, this Kensington property sold for £80m in 2008. There are many empty ‘offshore’ mansions in the capital. Photo: Ray Tang/Rex

George Osborne has the right instinct on tax. Get some sanity into child and housing benefit, relieve taxes at the bottom and, at the top, tax wealth rather than income. If so, there is no time like the present. The chancellor should drop the unloved 50% band of income tax and go for property. Housing is the most inefficient, mal-distributed, under-taxed and therefore overpriced asset in the land. Tax it properly, with something in return.

Britons live more lavishly than any other big nation in Europe. More live in houses not flats, more have private gardens and more are home owners not renters. They also pay the lowest local taxes. What they do pay is a cockeyed, regressive, un-buoyant council tax, based on property valuations that bear little relation to actual or differential price. The top H band of council tax in the richer parts of the south-east embraces almost half of home owners. It is, in effect, a poll tax.

Year after year the last Labour government funked revaluing England’s council tax bands, meekly fearing that losers might howl louder than winners. The Welsh were bolder, revaluing in 2005 and now getting the benefit. Council tax on an I-band house in Gwynedd is higher than on a sheikh’s palace in Kensington (£2,870 against £2,158).

The Liberal Democrat answer is Vince Cable’s £2m mansion tax, an impost with built-in political impossibility. It is swingeing, posited at £20,000 a year per mansion. It has a blatant cliff-edge effect, excusing houses just below the threshold yet savaging those above it. It evokes the “granny tax” protest, lacks regional variation and is merely a top-down fiscal wheeze to avoid the odium of rate revaluation.

Meanwhile council tax remains the fiscal Cinderella, a miserable drudge of a thing, abused, beaten and kept in the localist broom cupboard. It was conjured into being by John Major’s government in 1992 to purge the Tories of the stain of poll tax, while somehow pretending it was not a reversion to the rates.

Council tax is unfair. Whereas under rates, the ratio of lowest to highest house valuation was roughly 1:100, the spread of the eight council tax bands is merely 1:3. The highest H band was £320,000 at 1991 prices (up to an average of £950,000 today). The bands have never been adjusted, while a growing sense of unfairness leads all governments to curry electoral favour by “freezing” council tax in favour of stealth taxes. The whole saga epitomises Britain’s political cowardice.

Osborne should follow gutsy Wales and introduce new upper bands that reflect the rise in house prices since the 1990s. He could do it now. Only the existing H band would need revaluing, and could be graduated in three stages to whatever value he chooses. The actual tax paid per band would still be determined by local councils. The allocation of properties to the new bands by currently under-employed estate agents would be no big deal. It must anyway be undertaken one day.

Property is the easiest of all assets to tax because it the most visible, most recordable and most unavoidable. The private housing lobby is already hollering about losers, crying that any new top bands will “unfairly target the income-poor and equity-rich”. This is like worrying about people who own Rolls-Royces they cannot afford to drive.

The genteel poor may use inherited property inefficiently, but there is no reason for not taxing them for doing so. I cannot plead to be excused taxes because I get little benefit from them. The government is now proposing to “tax” housing benefit to reflect the number of rooms recipients leave unoccupied, and to discourage them from living in expensive properties. Taxing the living space of the rich is hardly unfair.

Another group of much-bewailed losers is foreigners, many of whom pay neither taxes nor stamp duty. They can lump it. On one estimate, some 100,000 UK properties are now parked in offshore tax havens, which must comprise the bulk of the 155,000 houses in England and Wales thought to be worth more than £1m. Why Gordon Brown left in place this massive tax loophole, costing some £1bn a year, is a mystery.

Nor are Britain’s property taxes particularly high. New York’s are fixed at between 1% and 2% of value. Westchester County’s median property tax is $8,474, roughly three times the top rate in London’s Kensington. Many New Yorkers pay $20,000 to $30,000. These can be partly offset against other taxes, but taxes they remain.

There is another reason for raising taxes on property across the board. The biggest unexploited – and “greenest” – housing resource in Britain is empty and under-occupied property. There are empty rooms over shops, frozen by planning control. There are empty “offshore” mansions in central London. There are low plot ratios under urban renewal and more vacant commercial sites than ever. Britain is wasteful of residential land. An estimated million vacant homes are said to lie hidden within the urban and suburban landscape of Britain. Osborne is right to regard planning as one inhibitor of bringing them into use. Tax relief on residential lets would also help.

The key here is to use the tax system as an aid to urban growth, properly so called. City sprawl is now a Europe-wide problem, with car-intensive building in the countryside increasing by 20% since 1980 to meet a population rise of just 6%. It may be impossible for a free market to “monetise” the value of open country for leisure and recreation, but it obviously makes sense to direct taxes at ensuring developed land is used more efficiently. We should tax its extravagant use and relieve taxes for public benefit.

There is no denying the political price in progressive property taxes. The rich will pay more. But that price could be balanced by abandoning the 50p income tax band, which history suggests will raise little extra money. The net increase in revenue from council tax could then be diverted to the Liberal Democrat goal of a higher basic tax threshold. Each of these fiscal changes should yield pleasure somewhere on the political spectrum, while also delivering the chancellor a possible rise in overall revenue.

Those who champion fiscal reform get precious few moments on stage. They no sooner start their song than they are deafened by cries of political expediency. This time the politics could just be in their favour. Might someone listen?

THE RENTIER CLASS DIVIDES AND RULES

In an interesting “Ockham’s Razor” program on the ABC’s Radio National on 28 February 2012, the noted science writer Ann Moyal called for “interdisciplinary approaches” between science and the humanities to assist in solving our problems. That would indeed represent an improvement, because at times the difference is a rather contrived one.

She mentioned CP Snow’s famous 1959 Rede Lecture “The Two Cultures” which even then noted the widening lack of communication between science and the humanities.

I have a slightly different take on the matter. The division between science and the social sciences has served the rentier class so well, it’s not going to permit without enormous resistance the collaboration Ann Moyal seeks.

You see, it was not by accident the 0.1% removed the classical science of political economy from the category of science and dispatched it off into the humanities, repackaging it as a neo-classical economics where land and capital have become one and the same.

By explaining how the kleptocracy was capturing the public’s land and natural resource rents unto itself and taxing labour and capital instead for revenue, Henry George had come to represent a clear and present threat to the powers that be and his ideas had to be resisted at any cost via the universities.

The arguments of those opposed to Henry George were so obviously risible, self-interested and shallow that conclusive action had to be undertaken, and the universities must be the means.

It had to be falsely put about that the study of economics had no predictive capacity–as any science should–therefore it had to be recast as one of the humanities.

Mason Gaffney’s “The Corruption of Economics” provides a chapter and verse account of the personalities involved in this incredible perversion of intellectual rigour. Gaffney demonstrates the steps taken were clearly a stratagem to defeat the exposition of Henry George and his many predecessors and followers from again taking root in society.

Once the pea and thimble trick of the 0.1% had been exposed for what it is, the 0.1% was forced to defend itself by indulging in corrupt practice within the halls of learning.

Thus, ever since, has the cause and cure of rent-seeking and bursting real estate bubbles remained the blind spot for both science and humanity at large.

However, it is not only the bifurcation between science and the humanities which has progressed the blatant lie that leaves public education, health, welfare and infrastructure underfunded. It is also caused by the paranoia into which political parties have descended, mindlessly dividing societies. Perhaps the most obvious example is between Democrats and Republicans in America where ideologues continue to cast the most incredible aspersions at each other. This is democracy in action?

The common feature found in each of these false dichotomies is that people no longer matter: only finance, big corporations, the political parties–apparently an end in themselves–and real estate, of course, matter. For corroboration, one has only to look at what is occurring in Greece, the fount of democracy.

Wedges driven by the 0.1% between science and the humanities, and their economic falsehoods off which political parties feed without question have sidetracked and split democracies. And it has conducted this malfeasance with reckless aplomb – because it has the money; it has the rent.

We are in the end game. If ignorance and fear paralyse us now, the 0.1% wins again.

THE BANKS

I’ve said our ‘Big Four’ banks will no longer be with us once the $800 billion in the Australian bubble disappears with a ‘zap’. One must hope this is permitted to happen without taxpayers being shanghaied into forlorn attempts to bail them out for their incredible crime of lending like drunken sailors into the world’s greatest real estate binge.

I’ve said our ‘Big Four’ banks will no longer be with us once the $800 billion in the Australian bubble disappears with a ‘zap’. One must hope this is permitted to happen without taxpayers being shanghaied into forlorn attempts to bail them out for their incredible crime of lending like drunken sailors into the world’s greatest real estate binge.

Indian banks are much more circumspect. They know about risk management.

A ripple of concern shot through me for Ken Henry when I learnt he’d accepted a position on the board at the NAB.

There are obviously still bubble deniers. The Daily Reckoning Australia endeavours to wake them from their reveries today:-

The Bigger Banks Are, The Harder They Fall

By Callum Newman, Editor, The Daily Reckoning Australia

“Australia is a house of cards. We are confident the bubble will burst and that it will be spectacular…” – John Mauldin and Jonathan Tepper, Endgame

Keep the quote above in mind, dear reader, if you can forget it in the first place. It’s an important point. But first! “Five Reasons Aussies Should Feel Smug“, headlined Nicole Pederson-McKinnon in The Age this week. One of those reasons – the first no less – was Australia’s current low debt to GDP ratio.

It is a commonly cited observation when someone frames any discussion of the Australian economy. Very few, to your editor’s observation, qualify it by adding that two notable countries recently enjoyed the same condition: Spain and Ireland. They both had relatively low government debt, until they didn’t.

The reason these two countries no longer enjoy this advantage is they were both required to bail out their sovereign banking systems, both of whom had balance sheets full of quality assets, until they didn’t.

That this might happen to Australia seems an important point. Australia’s risk is concentrated into four big banks, who have in turn concentrated their lending to one sector: residential housing.

The fact that there are four big banks and not twenty little ones is where the fault lies, or first appears. A financial system is a lot healthier with smaller institutions. That, at least, is one of the conclusions of James Rickards in his book, Currency Wars.

Or as he puts it:

“The solution is a mixture of descaling, compartmentalization and simplification. This is why a ship whose hold is broken up by bulkheads is less likely to sink than a vessel with a single large hold. This why forest rangers break up large tracts of timber with barren firebreaks.“

To him Australia, with its “Big Four”, must look like a forest of parched trees and dry pine needles doused with kerosene: a fire hazard, and probably a moral one, too. It certainly looks that way to John Mauldin, as the quote above makes clear.

“As a consolation to mortgage holders, the RBA has a loaded gun if it needs to shoot its way out of another crisis,” wrote Nicole Pederson-McKinnon: high interest rates being the third reason Aussies can feel smug. The fact that Aussie banks did not follow the RBA’s last interest rate cut did not get a mention.

It’s well worth making the point now, because Australian banks look rock solid to most people. Until the day they don’t.

RICH CHEAT

Once you’ve clicked on “No! Impossible!”, you might want to understand their main pea and thimble trick.