NONE SO BLIND …

This letter to the Australian Financial Review epitomises what’s wrong with Australia.

The BIG winner is Mr Palmer.

http://media.crikey.com.au/dm/newsletter/dailymail_9ca729524a2832b4f6677b5e9ccfec51.html

It’s not all about GST: why land tax should be on Hockey’s agenda

JASON MURPHY

Economist and former Australian Financial Review reporter

New truths lie at the centre of the tax debate in Australia. If you weren’t paying very close attention, you might have missed their introduction.

Top echelons of tax policy now take as given the following ideas:

This technocratic takeover of the tax agenda is global. It has come about over several years, led by the likes of global consultants PwC and economists at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. In Australia it has found support in Treasury (and The Australian Financial Review).

In this context, possible changes to the GST aired this week should be seen neither a tweak as a sop to the states nor a passing fad. They represent a seismic shift in thinking on how best we should raise taxes. Like tectonic plates shifting and building up pressure, the change in thinking has built up over time.

In the Henry Tax Review the germ of the current thinking is visible. While arguing for keeping personal income tax, it advocated for “growth-oriented corporate tax” — code for lower rates. It also pushed for a land tax.

In preparation for the 2011 tax forum, the Business Council of Australia argued for reducing “reliance on volatile direct taxes in favour of more stable indirect taxes such as consumption tax and land tax”.

The argument for taxing immobile factors like land and supposedly immobile functions like consumption is motivated by the erosion of traditional tax bases.

Developed countries have been struggling to collect corporate taxes as production moves offshore and profit shifting makes millions disappear. An increasingly mobile global workforce also makes a dent in personal tax collection …

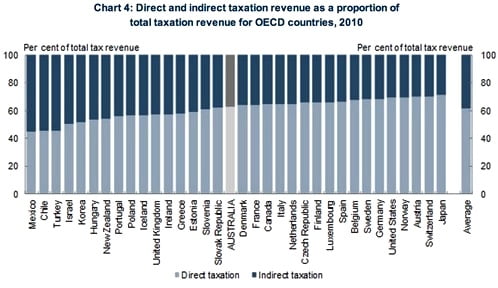

Australia is far from an outlier in its ratio of direct to indirect taxes (source: Treasury)

The argument for indirect taxes is established and now being made very close to the beating heart of government. Treasury Secretary Martin Parkinson said this week in a speech to the Sydney Institute:

“The share of direct and indirect taxes as well as Australia’s reliance on income taxes) has changed little since the 1950s …

“Research consistently says that reduced reliance on income taxes and increased reliance on other, more efficient sources of revenue, including indirect taxes, can support higher growth and higher living standards by increasing workforce participation and lifting productivity.”

Parkinson promised the white paper on taxation would be explicitly tasked to consider the mix of taxes, “including whether there is a role for a greater contribution from indirect taxes”.

Some relevant research has been done in Australia, but some of the research to which Parkinson refers relies on findings relevant to Europe.

An OECD paper describing a QUEST model simulation found that following a shift toward indirect taxes “there would be a positive impact on employment and output, even though for many salaried workers the gain from lower direct taxes would be offset by higher goods prices”. But the same paper admits that not all evidence points in the same direction:

“The example of the Nordic member states shows that high levels of taxation can be compatible with high employment and competitiveness levels. Nevertheless, ceteris paribus, reducing taxes on labour could be a useful tool to stimulate employment.”

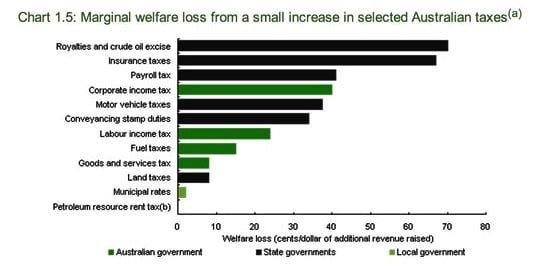

This is not to deny the sense of the idea, nor the good intentions of the OECD’s experts. Taxing things other than productive activity makes sense if your goal is to grow productive activity. This chart from the Henry Tax Review sums up why land tax and GST are preferred to payroll and company tax:

A question mark remains over whether indirect taxes can be as progressive as the personal income tax scales. But they need not be regressive.

Consumption taxes are useful because they raise revenue from those with a lot of wealth as well as those with a lot of income. The rich tend to spend even when their assets are returning low or negative income. And land taxes can be progressive, especially if they are designed with an appropriate rate and threshold.

Even if progressivity were maintained under a system of indirect taxes and radically lower income taxes, it would be less transparent and legible to the layperson than before. You can expect that to lead to a political barney over how to measure progressivity.

Not everyone has got the memo about the change in thinking. Here’s Alan Kohler late last year:

“While increasing the rate of GST and/or closing its holes should not be off the table, doing that would hit poor people the hardest. Increasing income taxes — gradually, over time — would raise more money and be fairer.”

The Greens are also keen on raising marginal rates, to 50% on incomes over $1 million.

These arguments still make sense and are easy for people to grasp. Years of focus on income taxes mean that’s what citizens expect to be in play when the conversation comes to tax reform. And those expectations circumscribe the freedom of politicians.

As Treasurer, Joe Hockey may be tempted by tax changes that could boost growth. But as part of the leadership of a government with a popularity problem he will find it difficult to implement what the technocrats expect. People are not yet ready for this. Evidence Hockey can sniff the wind came as he swiftly moved to deny that the government plans to lift the GST.

Of the two main indirect taxes, there is much more noise around the idea of a higher or broader GST. But should GST be sucking out all the political oxygen?

It is avoidable, as illustrated by the stink over online shopping thresholds, and by the incredible surge in the number of Australians spending their savings on overseas holidays. (In January, according to ABS trend measures, 753,000 Australians went abroad, a record number that represented 8.1% growth over the year.)

Land tax has the advantage of being one of the least distortionary taxes available, and has capacity to raise large amounts of revenue. But it lags far behind the GST in terms of public visibility.

In the ACT a land tax is being introduced to substitute for the wildly distortionary transaction taxes. Whether such a tax can establish a constituency beyond the policy-wonkish landowners of the ACT remains to be seen.

*Jason Murphy is a former Treasury economist and Australian Financial Review journalist. He blogs at Thomas The Think Engine.

Frank de Jong gives a compelling explanation in Toronto of why the world needs to levy economic rents, not taxes, for revenue.

I don’t think Reserve Bank of Australia chief, Glenn Stevens, would agree with you, Frank. You see, he represents the interest (in every sense of the term!) of the banks, NOT of the Australian people. He wants a greater GST on the people. Banks and businesses can claim GST back, but are unable to avoid land-based revenues.

Affordable education

How do we fund better schools?

Affordable infrastructure

How do we keep freeways free? How do we extend the rail system? How do we build bridges and conserve water? How do we decentralise?

Affordable housing

How do we keep a lid on escalating land prices (and therefore mortgages?) How do we make overseas investors in our real estate pay their fair share?

Affordable public health

Where’s the money to come from for better hospitals and preventative medicine?

Affordable social welfare

Is a universal basic income achievable?

Affordable defence and public security

How can defence and crime-fighting be funded adequately?

_____________________________________________

These questions are constantly argued quite intelligently, but they often end where the debate ought to begin. The terribly inadequate alternatives amount to: “There’s simply inadequate public funds for these tasks, so we must either cut administrative costs and introduce efficiencies, or else increase taxation.”

Few people call for the necessary revenue reform that will raise adequate funding for all our necessary requirements whilst significantly reducing costs and prices.

What’s changed that we used to be able to fund our necessary governance with a far smaller population? How did our forebears build roads, dams, railways, schools and public libraries?

We did it from taxes on property values–more properly, rents not taxes, because they can’t be passed on in prices like taxes–and we did it best from taxes (rents) on vacant land because that didn’t penalise you for improving your property.

However, since the peak of the Kondratieff Wave in 1972, it became increasingly fashionable for governments to move away from a reliance on increasing property values for revenues to be increased. As governments gradually moved out of capturing the economic rents from land, private interests moved in to capitalise privatised rents into increasingly higher and higher land prices. Banks have become the beneficiaries at a great cost to society. The phenomenon has generated several property booms and several busts that have become more and more alarming. Mortgages, debt and credit have grown concomitantly with these escalating land prices.

But no one is listening to the alarms. The question has become how can we do more with less? And it’s a quite stupid question.

The real question is how can we quickly return to greater reliance on land-based revenues instead of the welter of taxes that has brought economies to their knees and helped inflate land price bubbles?

Unfortunately, as we go further down the gurgler, very few are asking this critical question; only Georgists.

Australia might look to New Zealand for leadership in many things, head of Treasury Martin Parkinson, but not to increase our goods and services tax (GST).

Australia might look to New Zealand for leadership in many things, head of Treasury Martin Parkinson, but not to increase our goods and services tax (GST).

The GST was going to put an end to Australia’s cash economy and it has done nothing of the sort in the last fourteen years. Record amounts of GST are being avoided. If we increase the GST, honest people will pay more, but not those operating within the cash economy.

Let’s start at the beginning, Martin.

A comprehensive review of the tax system by your predecessor, Ken Henry, showed that 115 of our 125 taxes raise only 10% of Australian revenue. Why not abolish them, and all their bureaucracy and deadweight, Martin?

We have an ageing society, and an increase in income tax will simply bring forward the retirement plans for many people. So forget income tax increases.

Now, there is land tax, Martin. It is administered by lazy state governments who have thresholds, exemptions, multiple rates and aggregation provisions, all of which make a mockery of the equity of land tax. A single rate land tax, applied to every property in Australia–and we do have a site value assessed on every property–would be the most equitable source of revenue. This statement is supported by the KPMG-Econtech study of Australian taxes.

But you couldn’t rely on the states to reform their land taxes in concert, so why not abolish the mish-mash of state land taxes and re-introduce the federal land tax which was abolished in 1952 after 41 years? This would then be rebated back to the states on the basis of how much land tax revenue came from each state.

With the efficiencies engineered by the abolition of 115 taxes and the introduction of new federal land tax–where owners and tenants would pay their fair share–there’d be great scope then to abolish stamp duties and payroll taxes – both counter-productive taxes.

Martin, we could lead the world in establishing an honest and efficient tax regime. We don’t have to make the same mistakes as New Zealand.

And Treasury must come to see cause and effect of the boom and bust.

[ps. You’re right about an upcoming recession, although it’s actually a depression, Martin.]

Economic rents are really from the natural endowment–not high wages for specialist talents, as per neo-classical economists–but this article is heading in the right direction. And, yes, rent-seeking is entirely responsible for the growing wealth divide in society.

“And ye shall swell to an army vast,

And free men from the wrongs of the North and Past,

The land that belongs to you”

– Henry Lawson