Newspaper editorials seem mystified that retail spending is down. They point to the fact that Australia’s national debt, unlike other nations, is well under control, as though this is somehow germane to our commercial slowdown.

Editors also reflect that maybe online shopping is responsible for cutting a swathe through spending in the shops.

In an obvious attempt to be optimistic, there’s no mention of the world record ratio of household debt to disposable income, i.e. above 150 per cent, to which Australians have shackled themselves in recent years.

Many people have hit the stumbling block and been forced to cut back on their spending, but others, aware of the catastrophic effects of the financial collapse overseas, have set themselves on a debt reduction program. Accordingly, a slight downturn in the ratio nearer to the 150 per cent mark shows their efforts are beginning to work. Unfortunately, such reduction in household debt doesn’t assist our economic performance.

Surely then Australia’s world record household debt levels explains the collapse in consumer confidence and demand? Mortgage debt, of course, accounts for by far the greatest part of household debt, and credit cards for much of the rest.

So, how does politics’ Left respond to this unwelcome slowdown?

Unions are looking for pay rises for their workers. They say this will help relieve their members’ debt and might get them spending again. The unions are aggrieved Qantas wants to put off 1000 staff to restructure towards Asia and at OneSteel’s announcement of job cuts, and they know more can be expected in retail if things don’t change. So, more money in workers’ pockets will resurrect economic activity, they claim. And they’re partly correct.

Meanwhile, marking the 20th anniversary of the Superannuation Guarantee Levy, former Prime Minister Paul Keating notes that unit labor costs decreased every year the levy rose, from 4 per cent in 1991 to 9 per cent in 2002, despite employers claiming it would prove to be a cost to them. He’d like it increased to 15 per cent, but will settle for 12 per cent immediately.

Mr Keating apparently hasn’t noticed average weekly wages have trended down ever since 1972. (Some apparent real increases since 1998 were at least partly the result of redefining Australian CPI following the US Boskin Commission’s recommendations in 1996, wherein it opined the CPI had been overstated, and employed more stable “rental equivalents” in preference to house prices.)

As Paul Keating dusts down his Louis XVI clocks, one wonders whether he has workers’ interests at heart, or just his own place in Australia’s economic history. Isn’t workers’ most immediate need in hard times to be able to access their own earnings? Isn’t compulsory superannuation based upon the incredibly patronising premise that governments and super funds know better than you how to manage your retirement and financial affairs?

For that matter, now that the union movement itself has an integral stake in industry superannuation funds, wherein lies its true allegiance? Does it lie in making favourites out of particular shares, or certain REITs, or in looking after the here and now of its members, as once it did?

On the other hand, business is becoming choleric about the possibility of further wage increases. Salary rises have recently exceeded increases in productivity, they rightly claim, despite the longer trend in real average weekly wages having declined from the outset of the 1970s.

So, you can bet that industrial relations, which for employers amounts to keeping the lid on salaries if production isn’t also increasing, is again about to hit the headlines and become contentious. Like the unions’ logic that wage increases will help increase effective demand, that these should not be allowed to occur unless there is a corresponding increase in productivity also seems a valid proposition. Both sides are partly right.

However, as our economic performance worsens, the inevitable outcome of rapidly hardening attitudes between unions and business is likely to be greater strike action and IR conflict. Whilst this tension between labour and capital is age-old, neither side offers resolution to the immediate problem of ineffective demand.

If unions have their way with pay rises, it will be inflationary and put further pressures on business to reduce staffing levels. If business holds its line on no further pay rises, from whence shall effective demand arise?

If the current approaches of labour and capital can be seen not to address the problem, is there any alternative to these rapidly bifurcating attitudes? Must we find ourselves in one camp or the other?

Let us consider how to provide wage increases without adversely affecting business or generating inflation.

THE SOLUTION

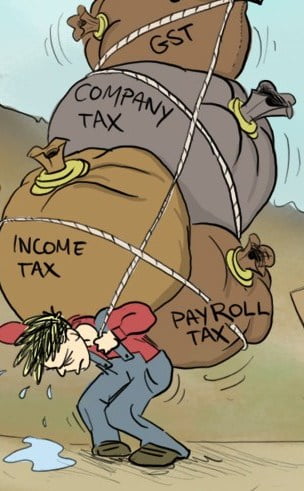

The Henry review of the tax system seems to offer the only solution for Australia. Ken Henry’s panel strongly argued the need to abolish many inefficient taxes that adversely affect business, increasing its costs and adding to consumer prices.

The tax inquiry showed a transition to a greater reliance upon natural resource rents and reformed State land taxes, both being in the nature of a community-generated surplus product, otherwise known as economic rent, won’t add to business costs if a greater part of it is captured to revenue coffers.

As natural resource-based revenues do not add to business costs is the one point on which all economists do agree, it’s a pity neither of the major parties has been prepared to take this up and educate the public to that effect. Vast ignorance exists on this critical point, and the parties remain fearful and delinquent in not mentioning it.

It is therefore clearly possible that tax cuts can deliver increased incomes both to businesses and consumers without being inflationary.

Is this not the solution to the impasse currently confronting unions, businesses and all Australians? Would not this action assist debt to be paid down whilst also restoring consumer confidence that the tax system is finally providing better signals, namely, that increased productive effort will be rewarded instead of punished?

If the public tax forum to be held in Canberra on 4th and 5th of October fails to grasp this nettle, Australia’s economic future appears certain to grow increasingly bleak.