WALLS THAT SPEAK

Like most modern cities of the western world, the architecture of the city of Melbourne relates fascinating stories of boom and bust. Almost every building tells a tale, either of the relative ease and timeliness with which it was constructed during the boom, or of the unforeseen financial difficulties with which it was plagued before it was finally able to be completed after the building bubble had burst.

Interrupting hiatuses are to be found between the various architectural styles during the 1890s and 1930s depressions and at the two world wars. But even this absence of construction, coupled with the buildings themselves, paint very telling pictures of Melbourne’s financial history, back to mid-nineteenth century days of the Bendigo and Ballarat goldfields and beyond.

Some examples:-

SPRING STREET MELBOURNE (TOP END OF BOURKE STREET)

Work commenced on Victoria’s State Parliament House in 1856. It was designed with a glorious crowning dome as shown here:-

But ended up looking like this:-

What happened? The recession of the 1870s and the depression of the 1890s happened.

The absence of the dome today continues to mock Victorian parliamentarians’ lack of understanding of the theory of economic rent. Ask any of them, and they seem unaware that taxing the State’s production, employment and exchange, instead of capturing its land rent, not only accounts for the missing dome on Parliament House, but explains economic recession and depression, and the lack of adequate funding for Victoria’s public transport, education, health, and public safety.

Their inability to get to grips with Melbourne’s financial booms and busts proves them either ignorant or stupid. They seem actually to prefer these repetitive ravages to a healed and ongoing healthy economy.

333 COLLINS STREET MELBOURNE

The Commercial Bank of Australia was completed at this address in 1891 but temporarily closed its doors shortly thereafter in 1893 to panicking depositors during the 1890s depression. The Commercial Bank of Australia eventually merged with the Bank of New South Wales in hard times in 1982 to become the modern Westpac Bank, which itself held on only by the skin of its teeth from the 1991/1992 recession.

From 1990 to 1991, just after the 1980s boom had peaked, a magnificent 33 storey building in classical post-modern American style was erected on the extended site, for which a record $2139 per square foot was paid. The massive original banking chamber dome was retained and integrated into the design in a complex engineering feat by the builder, Becton Corporation.

But things went horribly wrong in the recession of 1990/1991. Becton had fortunately insured itself and ended up exercising 90 per cent of its put option of $512m with the State Government Insurance Corporation of South Australia (SGIC). However, the SGIC hadn’t adequately covered its own position, sending broke the State Bank of South Australia. The State Savings Bank of Victoria also collapsed as a result of its thrusting but inexperienced merchant banking arm, Tricontinental, which helped fund the development it had intended to occupy.

The premier of South Australia, John Bannon, was forced to resign in 1992, and the Labour Governments of Victoria and South Australia were defeated at respective elections in 1992 and 1993.

The 1980s bubble was certainly bigger than 333 Collins Street, but this was the building that brought down the governments of South Australia and Victoria.

Tricontinental sent the State Savings Bank of Victoria (SSB) broke, and it was taken over by the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA). The CBA then proceeded to move its headquarters into the SSB’s near-new headquarters at the south-western corner of Bourke and Elizabeth Streets which has only recently been refurbished to 21st century ‘green’ standards.

563 BOURKE STREET MELBOURNE

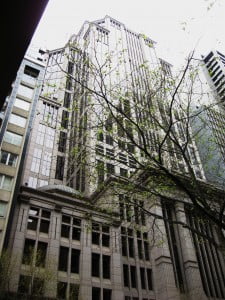

A 15 storey office building was constructed behind, and as part of, the historic five storey Gollin Building located at the south-west corner of Church Street in the city of Melbourne’s west.

It was built by restaurateur-racehorse-owner-developer, Floyd Podgornik, who tragically shot himself on the eve of the Blue Diamond Stakes in February 1990. In 1991, construction of the ‘Renaissance Building’ was completed at a total of some $84 million, including purchase of the land and the pre-existing Gollin Building. However, it was to be sold for about one quarter of this cost about 1992/93.

At the time, Melbourne’s skyline boasted a number of such new high-rise office buildings. Almost one third of them were vacant, with approximately one million square metres going begging – an amount equivalent to twenty Melbourne Cricket Grounds.

Although most landlords brazenly retained high nominal asking rents, leases were being written with associated deals of up to ten years rent free. Many of these included free fitouts to the tenant’s requirements which, when also taken into account, discounted nominal asking rentals by as much as four-fifths.

270 KING STREET MELBOURNE

WH Holmes House, a building of 16 storeys was erected on the site by Mainline Corporation in 1974 and occupied on completion by part of the Australian Taxation Office. Mainline was Australia’s biggest office builder when the company collapsed just before the final touches to the building were finished.

Commercial and General Acceptance (CAGA), the finance arm of the National Bank of Australia collapsed contemporaneously with Mainline Corporation, to herald Australia’s 1974/75 recession.

-oOo-

The buildings of the city of Melbourne are replete with such stirring stories. It’s entirely possible that future Melbourne development and infrastructure could be built with economic certainty via a state revenue system that collected a much greater part of land rent and far less taxation – absent the rampant speculation that puts so much construction at risk every second decade. But moneyed interests won’t countenance such a recession-solving solution and, unfortunately, they have the ear of our governments.