The following article is to be published shortly in the widely-circulated Chinese “Journal of Translation from Foreign Literature of Economics”.

The following article is to be published shortly in the widely-circulated Chinese “Journal of Translation from Foreign Literature of Economics”.

Financial Rules for Constructing a Strong State

Fred Harrison

China is now in the unique position of being able to learn from the tragedies of Western nations, to create a post-capitalist society based on the freedom and equality of all citizens. This can be achieved if the financial system is constructed on respect for the division between what the individual citizen may retain as private property, and what must be recognised as the property of society. Western nation-states failed to honour that distinction. The result was the evolution of politically Weak States, which were hostages of a statecraft based on greed.

Property rights, and their impact on the distribution of a nation’s income, were long ago recognised as being at the root of socially significant problems (like the division of the population into classes, the institutionalisation of poverty, and systematic degradation of natural habitats). That is why Western political philosophers wrestled with the problem of property ever since the ancient Greeks. They attempted to identify the terms on which to combine a strong State with freedom of the individual. How can power be shaped to serve the best interests of both the individual and of the State? Ancient civilisations failed to develop solutions of the kind that could sustain their societies.

Plato, in his Republic (Chapter 5), chose to avoid the problem by abolishing property. The power to make decisions would rest with the people who were trained as the guardians of society. In this utopian state, the people had to trust the guardians to act for the common good. But no society has succeeded in creating sustainable arrangements in which private property was abolished. So the problem of how to reconstruct power remains with us. Effective reforms are impossible without first understanding why private property is the cause of problems like endemic poverty. Before we can elaborate an answer to that question, we need to define what is meant by a strong State.

A strong State is one that is not vulnerable to manipulation by influential groups. Or, to put it another way, a strong State is one in which the population is composed of citizens who are equal. No one group of people can exercise undemocratic influence to secure privileges at the expense of others.

Military power is not an indicator of a strong State. A State that relies on coercive power to maintain order is in a weak position. It is a weak State because it has to either use force to control its citizens, or to deploy force against other nations to capture natural resources to satisfy the demands of its social elites.

A Strong State, then, is one that evolves on the basis of three principles.

- It does not need to exercise coercive power over its citizens to maintain civil order.

- It is authorised by the people to administer civil society on the basis of treating everyone as equals, as determined by the principles of natural justice.

- Its mandate is to produce and renew the social infrastructure that people, as individuals, cannot provide for themselves.

Nation building is complex. Social equilibrium, expressed as a practical balance in the distribution of power, needs to be achieved between the public and private sectors in the economy, between government and the population in politics, between materialism and morality in aesthetics. This means that freedom does not turn into anarchy, and order is not imposed by the tools of despotism. This ideal system has not yet been achieved in the West, and the principles for its achievement have eluded philosophers. That is why they have relieved themselves of their frustrations by seeking solace in utopian escapism. Can we now specify the conditions for emancipating the creativity of all members of society in ways that would constitute a fair and efficient system, as represented by our notion of a strong State?

The Role of Rent

At the heart of the challenge is the way in which a society owns and uses the resource that is needed to create and sustain the culture of the people. That resource is a flow of value, or income, which does not include

- the income needed to sustain the individual household economy; and

- the income needed to form capital, which raises the productivity of labour.

What is that flow of value called, and where does it come from? Through the genius of people in the earliest civilisations, a sophisticated market mechanism was created to identify that part of a population’s resources that were not the wages of Labour or the profits of Capital. In classical political economy, that third category is called economic rent. The earliest urban civilisations emerged when rents were reserved to fund the infrastructure required by complex settlements.

A healthy society achieves sustainable equilibrium when rents are allocated and used to fund the “common good”. It is when rents are privatised that society shifts towards despotism. So it is critical for the long-term survival of society that the correct rules are elaborated to

- measure and collect rents as they are produced;

- decide how to spend the rents; and

- guarantee everyone’s equal access to the benefits that flow from the expenditure of those rents.

By studying how a nation resolves these issues, we are able to infer the character of its culture. That information reveals the nature of personal freedoms, the quality of governance, how the natural habitat is treated, and whether the State is fit for its purpose of serving the whole population.

In Europe, about 500 years ago, a few people (the feudal aristocrats) began to appropriate the rents for their personal use. One result was the perversion of the two pricing mechanisms:

- prices charged in private markets for consumer goods, and

- prices (taxes) charged to fund public services.

By resolving the contradictions that create the tensions between these two pricing mechanisms, it is possible to integrate the public and private sectors so that they work together in harmony.

At present, people who earn their incomes by working in the private sector are hostile to government, because of what they perceive as the injustices associated with the taxes they pay. This creates social stresses that weaken the State. The objective of good governance should be to synchronise the two pricing mechanisms so that they complement each other. The goal is maximum satisfaction for individual citizens and the welfare of society.

The Volume of Rent

This thesis places a heavy burden on rent as a stream of revenue. So the first practical question is this: does a population generate sufficient rent to fund all the public services they need? There is no reliable answer to this question in the economic literature. Why? Most governments devote substantial funds to statistically measure activity in their economies, so why is the flow of rent as a percentage of national income a mystery? The answer reveals something important about the distribution of power in society. To work out the facts, we have to go back to the origins of the modern economy and the politics of State formation.

In the 17th century, an English philosopher, John Locke, wrote Two Treatises on Government (1689). This was a seminal document. It influenced the politicians who shaped the formation of the liberal State. It was quoted by the Founding Fathers of the United States of America. Locke argued that, in the state of nature, every person had a natural right to “life, liberty, and estate” (estate was the old English word for land). He argued that people consented to enter into civil society to protect their property. But nature – planet Earth – could not be privately owned. Why? Because people could only own as private property those things in which they had mixed their labour. So, viewed in terms of a flow of income, according to Locke there were two categories: the income of labour, and that share of income that could be attributed to nature.

To determine the legitimate distribution of income, we need to know the value that has to be assigned to the services delivered by nature (like the fossil fuels that yield energy that can be translated as the rents of oil, or of coal, or of the power of wind). On this issue Locke was less than honest. It appears that he did not wish to disappoint the aristocrats who controlled the public budget. For he claimed, in Chapter 5 of his Treatise, that the rent attributable to nature was just 1% of total income. The rest (99% of the flow of national income) was value created by the labour of the individual. He remained silent on the value created by the services of society. Today, the West’s economists claim in their textbooks that rent ranges from 1% to 6% of national income (drawing on USA data).

Nobel Prize economist Paul Krugman claims that, in 2004, the USA apparently generated “rent” of just 1% of total income (Krugman and Wells 2006: 283). Examples spanning the years since 1945 reveal how statistics were manipulated to under-state the quantum of rent.

Nobel Prize economist Paul Samuelson published the first edition of Economics in 1948. Charging rents for the use of natural resources, he explained, “may slow down their rate of depletion and serve to ration out such scarce, exhaustible resources. But in a freely competitive system, the self-interest of owners may well lead to the rapid using up of natural resources…. Unsightly and unhealthy slag piles may also be created…There may be deforestation that causes floods and soil erosion downstream…” (Samuelson 1955: 539). This is a scary prognosis! But aren’t these abuses of nature associated with the current fiscal regime, which largely fails to charge rent for the use of those resources? Samuelson does concede that “Pure land rent is in the nature of a ‘surplus’ which can be taxed heavily without distorting production incentives or efficiency” (1955: 535). But why bother to isolate rent as a special income category when the “Rent income of persons” is shown (on page 182) as just 3% of Net National Product? Not enough revenue here to fund public services!

In a later edition of Economics co-authored with a Yale professor, Samuelson reports the “Rent income of persons” as less than 2% of Gross National Product (Samuelson and Nordhaus 1985: 115). Drawing revenue from pure rents might be fair, and might be efficient, but the sum is obviously too trivial to target!

In 1963, Richard Lipsey’s textbook assured students that “an effective tax on economic rent would finance only a tiny portion of government expenditures” (Lipsey 1979: 371). Besides, there was a grave problem with the proposal: “The policy implications of taxing rent depends on being able in practice to identify economic rent. At best, this is difficult; at worst, it is impossible” (1979: 370, emphasis added). Real estate professionals perform this exercise every day for their clients, but in Western universities the students are taught that the task is impossible!

Heinz Kohler, a Germany economist, repeats the myths about not being able to isolate economic rent, and that rents would not yield sufficient revenue to cover government expenses (Kohler 1992: 857). His textbook is an example of the damage such manuals inflict on people who need to live in the real world. He claims that, when California imposed a limit on increases in the tax on real estate in 1978, by the mid-1980s “an unexpected consequence had emerged” (Kohler 1992: 859, n.13). For every $1 decrease in the property tax, property values rose by $7. Why were economists surprised at this outcome? Fiscal reformers predicted that holding down the property tax would translate into higher prices for residential land. They were correct. But for academics in their intellectual fortresses, this result could not be anticipated. So California’s voters were not guided away from what proved to be a disastrous decision for families who needed homes that they could afford.

The reality is that rent constitutes something like 50% of a modern nation’s income. How can we validate this claim?

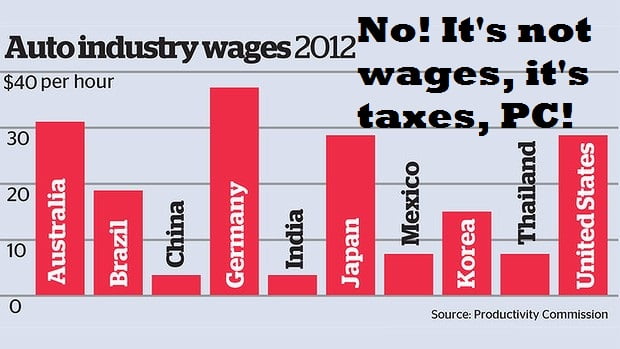

To excavate the truth, we have to return to the writings of John Locke. He examined the financial impact of taxes. In Some Considerations of the Lowering of Interest and the Raising the Value of Money (1691), he explained that it would be “in vain” for a country to impose taxes on anything other than land, for “there at least it will terminate”. The merchant won’t bear taxes, and the labourer on subsistence wages cannot bear them. So taxes are passed on, through the marketplace, in the form of higher prices. But someone must pay! Who? Locke was emphatic: taxes are ultimately drawn out of a nation’s rents (Locke’s reasoning appears in full in Harrison 2012: 184). This leads to an important economic insight. Taxes, if they are imposed on Labour and Capital to be paid out of wages and profits, reduce the income left in the hands of labourers and the owners of capital. This means they have less income left to pay as rent to land owners.

Locke’s thesis tells us something of vital importance about the nature of the revenue that is collected as taxes on labour and capital. In reality, that revenue is rent in disguise. We see the dynamics of this reality at work every day, as when a government reduces a tax on wages or profits. The net gain does not surface as higher real wages for labour, or real returns for capital. Through the competitive process, the gains are translated into higher rents paid to those who own the land.

In the past, land owners who controlled tax policy did not welcome Locke’s insight. They wanted to believe that, by cutting the Land Tax and imposing taxes on their peasant populations (such as the tax on the consumption of salt), they could reduce the share of the rent they paid to the State. That appeared to be the case, but it was all appearances. For, at the same time, the amount of rent the peasants could pay to their landlords was reduced. It was this struggle to control rent that caused social chaos in the form of mass unemployment, the under-production of wealth, debt and inflation and the division of the population into hostile classes. That struggle remains with us in the West to this day.

Adding up Rent

Locke’s thesis is most thoroughly explored by Mason Gaffney, who taught economics at the University of California. He formulated an acronym for Locke’s thesis: ATCOR. All taxes come out of rent (see Addendum).

The first step in calculating the size of a nation’s rents is to establish the amount people pay through “taxes” levied by government. In 2013, tax revenues collected by US federal, state and local governments added up to $5.3 trillion (GDP: $16.2 trillion). Using the ATCOR formula, we may conclude that, if America was a tax-free zone, this revenue would surface in the marketplace as rent. In other words, under present tax policies, about one-third of US income is transformed from rent into “wages” and “profits” via painful political illusions.

But if revenue collected by government is ultimately out of rent, why bother to collect that revenue directly? One reason is that collecting rent directly would raise the productivity of the population. Why? Because (to use the technical term) taxes cause “deadweight losses”. The gains from abolishing taxes on wages and collecting rents in a direct way to fund public services would have an enormous impact on people’s lives. Nicolaus Tideman, a professor of economics at Virginia Tech and State University, estimates that, after five years into the fiscal reform, the average American family would be better off by $6,300 (Tideman 2013).

Rents in Private Pockets

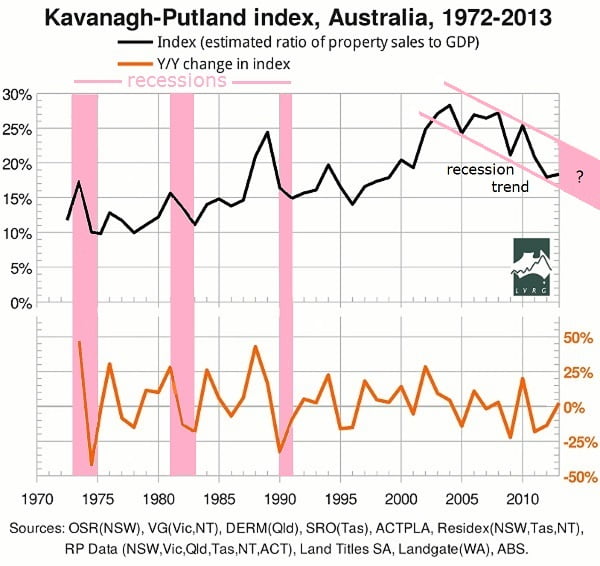

* The next question relates to the proportion of a nation’s revenue that is visible as rent. This is rent that is not collected by government. Western economists have no idea how much rent remains in private ownership. The prudent estimate is that rents in private pockets amount to about 20% of national income. In the UK, researchers found that rent was 22% of national income in 1985, rising to 29% in 1989 (Banks 1989: 40, Table 2:II). But 1989 was a peak year in the property cycle. Rents dropped in the recession of 1992. Allowing for the distortions caused by land speculation, the “normal” year estimate for the UK would be for 1987: 21.8%.

* In Australia, researchers – armed with one of the best official data sets in the world – calculated that rent in private hands in 2012 was about 24% of GDP (Putland 2013; Fitzgerald 2013). Rents in that year were inflated by abnormally high urban and commodity prices (this was one of the ripple effects of trade with China).

If we conservatively assume that privately collected rents are about 20% of national income, what would be a robust estimate for the value of all rents generated by mature industrial economies today?

If we take a random selection of 10 rich nations, ranging from Australia through the USA to Sweden, Germany and Japan, the average tax-take as a percent of GDP is 37%. In ATCOR terms, most of this is rent in its disguised form (collected as if they were “wages” and “profits”). If we add to this the rent that is not collected by government, of around 20%, we discover that rent exceeds 50% of national income. This first approximation of rent needs to be adjusted.

- Taxes distort the total income. They encourage the under-use of urban land (which artificially raises rents). Tax policy also motivates behaviour in ways that damage the environment, as when polluters are not obliged to pay for dumping waste into the atmosphere (which artificially reduces rents in some urban locations).

- A small part of tax revenue may actually come out of wages, because the workers lack the bargaining power to shift the taxes onto rent.

- Revenue currently collected by the property tax falls largely on economic rent.

Taking such considerations into account, we may cautiously estimate that rent is about 50% of total income. This is more than sufficient to cover existing government financial obligations.

History and Public Finance

Citizens are intuitively aware that there is something fundamentally wrong with tax policy. In England a thousand years ago, the State’s revenue was exclusively from rent; 500 years ago, the land grabbers got to work. The chart below tracks the reduction of rent as a proportion of public revenue. It records how England became a weak State with a dishonest form of governance. Evidence of this weakness can be inferred from the way land owners exercised power to manipulate laws to secure special privileges from the State.

Europe’s weak States were responsible for two world wars. And yet, the knowledge needed to avoid such outcomes was available to statesmen in the 18th century. The Industrial Revolution made it possible for everyone to prosper. What went wrong may be illustrated with the work of Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767-1835), a civil servant who established the University of Berlin. In The Limits of State Action, first published in 1852, he sought to describe how the State could be controlled.

Individual freedom, von Humboldt argued, was maximised when education was tailored to treat people as ends, not means. The State’s role was to help people realise their potential. But how could citizens constrain the State, which commanded the instruments of coercion? Von Humboldt is not convincing in his answers. According to my thesis, revenue is the key.

The State needs revenue to fund public services, as von Humboldt noted. But on what terms would that revenue be raised? Who decided how the revenue is raised, and how much is handed to government? The answers are to be found in the unique character of rent, and the social function performed by the land market. Through that market, the people themselves negotiate the rents they are able to pay to use the ecological and social services available at each location. By this process of free negotiation, who paid, and how much they paid, is determined by citizens, not politicians or servants of the State.

In the 18th century, the French Physiocrat school of philosophy explained that rent was the correct source of revenue for the State. Adam Smith repeated this recommendation in The Wealth of Nations (1776). But while von Humboldt confessed his “ignorance of everything concerned with finance” (1993: 134), he felt free to pronounce on tax policy. The Physiocratic rent policy was “unquestionably the simplest” way to raise revenue, he wrote, but “human power” must also be “subject likewise to direct taxation” (1993: 135: emphasis added).

If people like von Humboldt, who contributed to Germany’s zeitgeist, had helped to shape the State according to Physiocratic financial principles, that nation would have travelled a different path of social evolution. If everyone in Germany had enjoyed increased prosperity and social security, this happy state of affairs would not have led to the colonial land grab in Africa in competition with other European States (especially the UK, Spain, Portugal and Italy). It was that muscle-flexing mission which (among other reasons) was responsible for drawing a weak German State into war with its neighbours in 1914.

Transforming the Weak State

By restructuring the public’s finances, economic growth would be raised above historic rates. The important gains would take the form of

- more leisure for people,

- the freedom to deepen human relationships, and

- a stronger cultural membrane which wraps everyone in its riches (like the arts).

Politics would mutate into an authentic democratic process. Politicians would no longer be able to buy votes by funding projects which favoured special interests groups. The State would be strengthened on foundations of fairness.

In the West, the trend is in the opposite direction. In the 1980s, the trans-Atlantic nations began to shed their industrial status in favour of a rent-seeking culture. Whole populations now have to try to survive by participating in the arts of cheating. One example: the middle-class exercise in buying and selling houses to accumulate capital gains. This is a culture of cheating because it enables some people to live off the labours of others.

The Western State treats the land market as a slush fund. Either directly or indirectly, this rewards corrupt behaviour in the financial sector, in the media, law-enforcement agencies…. and, of course, in politics. The law on property rights legitimises the transfer of the common wealth to the privileged few, resulting in the rape of culture and the environment. An authentic democracy would not tolerate this tragedy. The People’s Republic of China need not become a victim of this social pathology, because it has passed a law which reserves land as public property. Its next step must be to guarantee that the rent that represents the services of nature and society are collected for the benefit of everyone in society.

Addendum

Mason Gaffney’s Writings

Mason Gaffney’s articles, essays and book chapters are accessible on www.masongaffney.org On the ATCOR thesis, see the following:

Mason Gaffney (1999), “Gains from Untaxing Work, Trade and Capital by Uptaxing Land”, Global Institute for Taxation (GIFT) conference, St. Johns University, New York, October 1.

” (2008), Keeping Land in Capital Theory: Ricardo, Faustmann, Wicksell and George, Am J of Economics and Sociology, Vol. 67(1).

” (2005), “A Better Way of Gauging Excess Burden of Taxation”, Working paper – published in Moss (ed.), 2006.

” (2006), “A simple general test for tax bias”, in Laurence S. Moss (ed.), Natural Resources, Taxation and Regulation, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Gaffney, Mason (1994), in Mason Gaffney and Fred Harrison, The Corruption of Economics, London: Shepheard-Walwyn.

Mason Gaffney (2013), The Mason Gaffney Reader: Essays on Solving the “Unsolvable” (2013).

Prof. Gaffney explains the ATCOR issue on this video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nLUGEMu9-sA&feature=c4-overview&list=UUpBfQyuQ1N5YMFsWnS26kfw

References

Banks, Ronald (1989), Costing the Earth, London: Shepheard-Walwyn.

Fitzgerald, Karl (2013), Total Resource Rents of Australia, Melbourne: Prosper Australia.

Gwartney, Ted (n.d.) www.henrygeorge.org/ted.htm

Humboldt, Wilhelm von (1993), The Limits of State Action, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

Kohler, Heinz (1992), Economics, Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath.

Krugman, Paul, and Robin Wells (2006), Economics, New York: Worth Publishers.

Lipsey, Richard G. (1963), Positive Economics, 5th edn. (1979), London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Putland, Gavin R. (2013) http://blog.lvrg.org.au/2013/07/economic-rent-of-land-as-fraction-of-oz-gdp.html

Samuelson, Paul (1955), Economics, 7th edn. (1967), NY: McGraw-Hill.

” and William D. Nordhaus (1985), Economics, 12th edn., NY: McGraw-Hill

Tideman,Nicolaus (2013), http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nLUGEMu9sA&list=TLW0JGVneIS95R2aRx8hoZCNBrzeZkGKZG

Fred Harrison is a graduate of the Universities of Oxford and London. He is the author of many books on the economics of rent, including The Traumatised Society (London, 2012). He is Research Director of the Land Research Trust, London. He was the economist who gave a 10-year forecast of the economic crisis that began in 2008. He warned the British Government in 1997 that the West’s house price bubble would peak in 2007, followed by a collapse that would trigger a global depression.